The American Horticultural Society at 100

The American Horticultural Society at 100

Looking back at a century of inspiring and educating American gardeners

By David J. Ellis

As the American Horticultural Society enters its 100th year, it’s instructive to place the organization’s founding in some historical context. In 1922, insulin was first successfully used to treat diabetes; Benito Mussolini became prime minister of Italy; the Egyptian tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun was opened by British archaeologists; James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses was published, and U.S. President Warren G. Harding made the first-ever presidential speech broadcast on radio.

It was in this period between the two great wars and prior to the Great Depression that two separate groups of idealistic gardeners—both professionals and amateurs—came together to form an organization dedicated to improving horticulture in America both as a science and an art form. The originating organizations were the American Horticultural Society (AHS) and the National Horticultural Society (NHS), which were founded the same year in Washington, D.C., and Henning, Minnesota, respectively.

One of the prime organizers of the NHS was Hamilton P. Traub, a botanist specializing in the amaryllis family, who conceptualized the idea of a national organization in a series of articles published in the Flower Grower magazine. Traub organized meetings among people with similar interests to his own, which led to the establishment of NHS in July 1922. The objective of the NHS was to promote “the increase and diffusion of horticultural knowledge, and the stimulation of universal interest in horticulture.” There was a general feeling that the NHS would play a similar role in America to that of the Royal Horticultural Society in Great Britain.

Traub subsequently became the first editor of the group’s publication, The National Horticultural Magazine, which has evolved over the years into our current member magazine.

The AHS was formed by a small group of dedicated horticulturists and plant scientists who gathered once a month in a building that is now part of the Smithsonian Institution to hear a lecture on horticulture. This group formally organized in September 1922, electing Albert F. Woods, a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) researcher, as president.

The two groups were aware of each other and, after brief negotiations, they merged in 1926 under the name American Horticultural Society, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. When Furman L. Mulford, a plant scientist with the USDA, took office as president, membership stood at 500 people.

The new organization continued publishing The National Horticultural Magazine, and Benjamin Yoe Morrison, an assistant to David Fairchild at the USDA at the time, took over as chairman of the magazine’s Editorial Committee. A legendary plantsman and hybridizer, Morrison later headed the plant introduction section at the USDA’s Glenn Dale, Maryland, facility and is perhaps best known for developing the Glenn Dale hybrid azalea series.

Morrison excelled not only as an editor and writer but as a horticultural illustrator. The linoleum block prints he created for the cover were the magazine’s hallmark, and his line drawings of daffodils and other plants frequently graced the interior of the magazine.

In 1934, Society headquarters were set up in the Washington Loan and Trust Building, where Morrison carried on his volunteer work as editor in his off hours from his official duties with the USDA. Under Morrison, the magazine soon attracted the country’s leading horticultural writers, including Mary G. Henry, Lester Rowntree, Clement G. Bowers, Frederic P. Lee, Edgar Wherry, and John Wister.

As the world hovered on the brink of war in 1938, Morrison was serving as both president of AHS and editor of its magazine. “Those years were difficult financial times for many organizations,” said John L. Creech, a former AHS president (1953–1956) and director of the U.S. National Arboretum, who died in 2009, “and the Society probably could not have survived without his many contributions.” During the war, the AHS and the Royal Horticultural Society jointly published a Daffodil Year Book. This project stemmed from the work of the Society’s Narcissus and Tulip committee, which had been publishing yearbooks from 1935 to 1938 in cooperation with the American Daffodil Society.

Post-War Transition

In 1948, as America moved into a post-war economic and social boom, the Society’s membership stood at less than 2,000 and its financial situation was shaky. At that time the AHS headquarters in Washington, D.C., was, as Creech described it, “a rented apartment above a flower shop across from the entrance to the National Arboretum.” Up to this point, the Society had existed mainly through the efforts of a corps of dedicated volunteers. “During that period some changes were made to try to bolster the Society’s status and membership,” recalled Creech, including “moving toward color photographs in the magazine, and hiring paid staff.” In 1951, a membership recruitment campaign was instituted for the first time. Morrison continued to edit the magazine until 1964, completing a 37-year tenure as the editor of what was then considered the most authoritative horticultural publication in America.

Another Merger

With the merger of the AHS and another major gardening group—the American Horticultural Council (AHC)—in 1960, the long-held vision of a national umbrella group for American horticulture was finally realized. Buoyed by the leadership of a who’s-who list of horticultural luminaries—including Donald Wyman, Henry T. Skinner, Russell Seibert, and Frederick G. Meyer, the AHS forged ahead with several significant projects.

Among the most significant was helping in the development of the first USDA Plant-Hardiness Zone Map in 1960. This was a landmark event, providing gardeners for the first time with detailed information on what plants would survive winter temperatures in different regions of the continental United States. The map was the brainchild of a 1953 AHC committee chaired by Skinner, the second director of the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., who served as AHS president from 1962 to 1963.

Another major project AHS took on was overseeing the AHS Plant Records Center (PRC) in 1968 at the Tyler Arboretum in Lima, Pennsylvania. Funded by grants from the Longwood Foundation, the project was the first attempt to computerize plant records for major American public gardens. This plan never came to fruition, however, because as computers became smaller and easier to use, public gardens discovered it was simpler to maintain their own records.

The AHC had initiated a Liberty Hyde Bailey Award in 1958, selecting John C. Wister of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, as the first recipient. The AHS has continued this award, positioning it as the most prestigious of the awards presented during the Society’s annual Great American Gardeners awards program. This year’s winner will be announced in March.

A Home at River Farm

In 1971, with David G. Leach, a renowned rhododendron breeder and author taking the helm as 22nd president, the Society relocated its offices from Washington, D.C. to a high-rise in Alexandria, Virginia. This move, precipitated by the need for more space to house a growing AHS staff, foreshadowed the Society’s next big step—the establishment of a permanent headquarters at nearby George Washington’s River Farm in 1973.

River Farm was not only a storied property, having once been part of the first president’s vast holdings, but a beautiful site, with formal gardens, mature trees, and grassy meadows sloping down to the Potomac River. After years of existing out of cramped offices and borrowed facilities, the Society had finally found the showplace for American horticulture that had always been a dream.

This came about through the generosity of New York-based philanthropist Enid A. Haupt, who provided $1 million to purchase the property for the Society. It also occurred as the result of an odd twist of fate. When the 26-acre estate, then owned by the Matheson family, initially came on the market in 1971, the Soviet Union offered to buy it for use as a retreat for its Embassy staff.

The prospect, during the height of the Cold War, of one of George Washington’s farms becoming the possession of the Soviet Union led to a public outcry. Even though the U.S. State Department proactively vetoed the sale to the Soviet Embassy, Haupt decided that the property needed to be preserved.

On a glorious, sunny first of May in 1974, some 500 guests attended the headquarters’ formal opening ceremonies. Among the luminaries at the celebration were First Lady Patricia Nixon, as well as Haupt, Leach, and AHS Executive Director O. Keister Evans.

In a 1973 New York Times article, Leach predicted that River Farm would become a national center for horticulture. “Now we can invite all the professional horticulture societies to become tenants,” Leach added. “We could share staff, equipment, and information so we could spend more time and money on the important things.”

Finding A National Voice

Bolstered by the transition to a showcase headquarters site and energetic leadership, over the next couple of decades the AHS enjoyed a growth spurt, with membership going over 20,000 in the early 1980s. During that time the Society began to champion children’s gardening causes, established partnerships to publish authoritative garden books, debuted its Reciprocal Admissions Program to encourage public garden visitation, and expanded its

Travel-Study program of international garden tours.

The AHS initially partnered with Macmillan Publishing in 1989 for the publication of The AHS Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. In the early 1990s, a new partnership with Dorling Kindersley Publishers led to the publication of a series of popular garden books and encyclopedias, including the best-selling AHS A–Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants, published in 1997 and reissued in 2004.

In 1993, the AHS organized its first National Children & Youth Garden Symposium, held in Chevy Chase, Maryland. The symposium was organized by Maureen Heffernan, the AHS education coordinator at the time, with the support of AHS President George C. Ball Jr. and sponsorship by the W. Atlee Burpee Company. “We saw an opportunity to play an active role in nurturing the next generation of gardeners,” says Heffernan, who is now executive director of Myriad Botanical Gardens in Oklahoma City.

More than 500 people attended that first symposium, and this enthusiastic network of educators has made the event an annual fixture that has been hosted in cities throughout North America. The 30th-anniversary symposium will be held in Richmond, Virginia, this summer.

In addition to the symposia, the AHS has supported youth gardening through model children’s gardens created at River Farm, sponsorship of the Jane L. Taylor award to recognize worthy individuals and groups involved with kids’ gardening, and development of The Growing Connection, an international educational program for middle-school students established in 2003 in partnership with the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

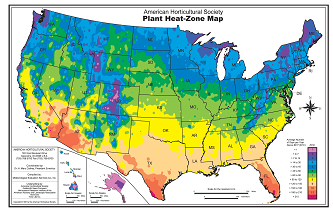

In addition to its publishing program, the AHS expanded its outreach to home gardeners through its official magazine, website (launched in 1998), and projects such as the AHS Plant-Heat Zone map, released in 1997. The map—conceived as a companion to the USDA Hardiness map—was the brainchild of AHS President H. Marc Cathey, who in the record-breaking global temperatures recorded during the 1990s saw the need for a tool that gardeners could use to select plants based on their ability to tolerate hot weather.

Cathey, who became AHS president emeritus in 1998, also spearheaded the development of the groundbreaking AHS Smartgarden™ program, initiated in 2000. The program offered gardeners earth-friendly advice on how to work with, rather than against, nature to create and maintain a beautiful landscape. In 2003, the program went nationwide via a series of four Smartgarden books tailored to different regions of the United States.

Cresting the Millennium

The early years of the new millennium were a busy time at the AHS, as Katy Moss Warner, who served as president and CEO from 2002 to 2006, teamed with Cathey to promote gardening as a path to environmental stewardship. Warner, a long-time AHS Board member who had been director of horticulture and environmental initiatives at Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida, for 24 years, brought energy and wide-ranging connections in the horticultural industry to her role. She used these connections to forge partnerships with events such as the annual Epcot International Flower & Garden Festival, where the AHS participated in a lecture program.

In 2004, Warner launched the AHS Garden Schools, an educational program featuring well known horticultural experts who traveled to different sites around the country. Cathey and Warner also spearheaded the AHS Green Garage program, which promoted environmentally sustainable gardening products and techniques. A model Green Garage display was exhibited at national events such as the Philadelphia Flower Show and the Northwest Flower & Garden Show in 2005 and 2006.

Following Warner, who retired in 2006, was Tom Underwood, who served as executive director for 10 years. During this period the Society debuted a gardening webinar series, upgraded its website, and entered a new book publishing partnership with Mitchell Beazley/Octopus publishing. Resulting books included the AHS Encyclopedia of Gardening Techniques—originally published in 2009, with new editions in 2019 and an upcoming Centennial edition this year—and Homegrown Harvest, published in 2011 with a second edition in 2013. Underwood also focused on River Farm’s infrastructure, securing funding for needed upgrades to the property’s water, septic, and communications systems. He sought out partnerships with organizations such as America in Bloom, the National Pollinator Garden Network, Seed Your Future, and the Coalition of American Plant Societies to enhance the AHS’s educational outreach.

Path Forward

Following a recent period of uncertainty for the AHS and River Farm, in which River Farm was put up for sale and other paths were considered for the organization, the current Board of Directors and members of the AHS community have rededicated themselves to remaining at River Farm and creating a stronger, more inclusive organization. As Board Chair Marcia Zech says, “Going forward, together, we have the potential to expand and build on this success by implementing a new strategic vision that enhances River Farm while propelling AHS forward to achieve its full potential as a visionary leader in American horticulture for the next century and beyond.”

This history was compiled by Editor David J. Ellis.