THE HISTORY OF RIVER FARM

River Farm’s amazing history includes archaeological traces of Native Americans who inhabited the land over 4,000 years before European contact, the history of enslaved people, and the little-known story of 19th-century abolitionist-minded Quakers who migrated to Northern Virginia.

Prehistoric to Colonial Era Indigenous Inhabitants

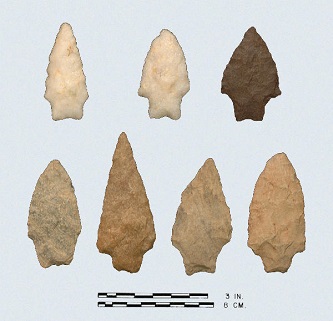

A 1987 archaeological dig at River Farm turned up significant evidence of prehistoric habitation. Some of the finds included a Halifax-style white quartz arrowhead at least 4,500 years old; a stone tool classified as a knife or Savannah River-style point from around 3,000 B.C. (similar to those pictured) and stone flakes left behind from making stone tools.

(Photo Credit: Virginia Department of Historic Resources)

Perhaps the most promising finds occurred on the bluffs, where Indigenous people had likely encamped to take advantage of the seasonal shad runs that amazed Capt. John Smith. Smith, who arrived with other Jamestown settlers, explored the Chesapeake Bay and lower Potomac for its abundance of fish. When Captain Smith came to the area, he mapped two major Native American villages along the Potomac, preserving valuable evidence of significant Virginia Indian activity at that time.

English Ownership

Known originally as Piscataway Neck, the first English owners of River Farm were the Brents, who were of both Indian and English heritage, and played an active role in the early colonial life of Maryland. Captain Giles Brent, Jr. was never at ease with the local Dogue tribe, or, it seems, anyone else. It has been stated that his encounters with the native tribe were a precursor to Bacon’s Rebellion, and at home, his relationship with his wife failed so miserably that it was she who obtained a legal separation in 1679, the first in the Commonwealth of Virginia. He returned to England where he died in September of that year. Piscataway Neck passed to a cousin, George Brent, and through him to a brother-in-law, William Clifton, in 1739.

Upon inheriting title to the land, William Clifton renamed the property Clifton’s Neck. By 1757, Clifton built a brick house on the property which the present-day 18-Century-style manor house serving as the headquarters of the American Horticultural Society now rests.

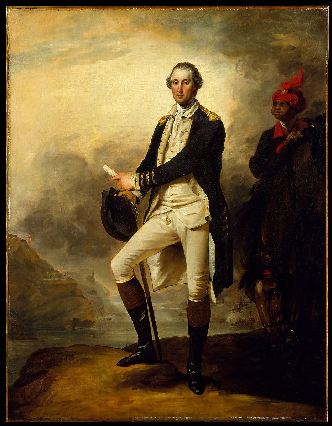

Purchased by Neighbor George Washington

Clifton suffered business losses and as early as 1755 advertised part of his holdings for sale. Gentleman farmer George Washington of neighboring Mount Vernon was desirous of buying this land, but because of what he described in his diaries as Clifton’s “shuffling behavior,” it was not until 1760 that Washington obtained clear title to the 1,800 acres for payment of £1,210 at the equivalent of a bankruptcy sale. To be fair to Clifton, not all the “shuffling” was his fault. At Mrs. Clifton’s insistence, only a portion of the property was first offered, the house and surrounding land to be retained for the Cliftons’ use. Washington refused to buy the reduced package. It was not until Clifton was forced to submit to a commissioner’s sale — Washington was a member of the commission — that Washington acquired the entire property and changed its name to River Farm.

Thus, River Farm became the northernmost of Washington’s five farms, and today’s River Farm is located on the northernmost division of that property. Although Washington had patiently pursued the acquisition of the property, he never actually lived on or worked the land. Instead, he preferred to rent it, first in 1761 to tenant farmer Samuel Johnson, who paid ever-increasing amounts of his tobacco crop to Washington for the privilege. The farm was even once offered for sale in 1773, but instead, Washington held on to it and later gave its lease as a wedding present to one Tobias Lear whose bride, Fanny Bassett, was Martha Washington’s niece and widow of George Washington’s nephew, George Augustine Washington.

Lear had come to Virginia in 1786 on the recommendation of a mutual friend to be secretary to Washington and tutor to Martha’s two grandchildren. He was treated as a member of the family, taking his meals with them. He served Washington not only as secretary but as a personal confidant at Mount Vernon as well as in Philadelphia and New York while Washington served as the young nation’s first President. He was at Washington’s side when he died. In his will, Washington gave Lear use of the farm, rent-free, for his lifetime. Lear’s wife Fanny predeceased him, and he installed his mother-in-law and children at the farm while he preferred to reside in Georgetown. It is said he died there, a suicide, in 1816.

Tobias Lear had called the property Walnut Tree Farm. Today, in the meadow below the “ha-ha” wall, one venerable old black walnut tree still stands, a reminder of the 18th-century landscape that Lear and Washington knew. Another of River Farm’s trees that have strong associations with Washington is the Kentucky coffee tree, so named for its native origin and because its seeds were once used as a coffee substitute. Washington introduced the species to Virginia when he returned from one of his surveying trips in the Ohio River Valley and successfully germinated seeds he had collected there. There are several specimens of the Kentucky coffee tree at River Farm, descendants of those first trees grown by Washington.

After Tobias Lear’s death, the farm was occupied by two generations of the Washington family: George Fayette Washington, a nephew, and Charles Augustine Washington, a great-nephew. In 1859, a century after Washington purchased the property from Clifton, Charles Augustine Washington sold 652 acres of River Farm to three Quaker brothers, Stacey, Isaac, and William Snowden of New Jersey.

The Quakers and the Abolition Movement

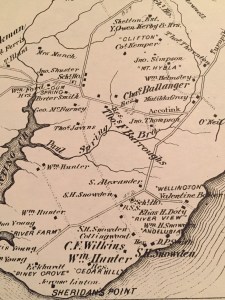

The Snowdens and other Quaker families came to the Woodlawn-Mount Vernon area in 1845, lured by the availability of hardwood timber bound for New England’s shipyards, inexpensive land, and the abolitionist spirit. Opening an early chapter in the South’s struggle for racial justice, the Quakers wanted to use River Farm to demonstrate to Southerners that farming could be profitable without enslaved labor. The Snowdens divided the acreage, then known as Wellington, into three sections.

The Three brothers: Isaac, William and Stacey Snowden lived on a farm in New Jersey with their Mother, Rhoda Hazelton Snowden, brother John, and two sisters, Abigail and Mary Jane. The Snowdens were Quakers and likely heard about opportunities in the Mount Vernon area through the Mullica Hill Friends Meeting where they were members. In the late 1840’s, Quaker families from New Jersey, New York and Philadelphia migrated to Virginia to purchase inexpensive farm and timberlands and to work with the free black community that existed in the area around Mount Vernon. They wanted to show that slavery was not necessary for financial success. In 1859, two years before the Civil War started, the brothers left home. While it is unclear whether Isaac, William and Stacey were previously acquainted with others that moved into the Mount Vernon area, they certainly worked in concert once they were neighbors.

As they left the Quaker enclave in Harrison Township, they couldn’t have imagined the lasting impact they would have on their new home. They purchased large tracts of land that had previously been part of George Washington’s River Farm and helped forge a community that would, for a time, carry their name (Snowden, VA). Their homes would be central to the development of roads, schools, churches, postal delivery, social and business organizations, recreation, and rail and steamboat travel between Washington DC and Mount Vernon.

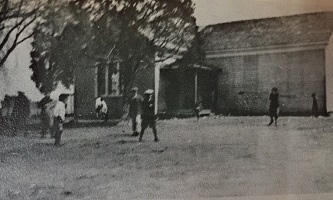

The Snowden School began at Wellington on River Farm (now home of the American Horticultural Society). In the early 1870s, the home was owned by Valentine Baker, a Quaker from New York. From 1872-1878 the school was operated out of the Baker home and served children from neighboring farms.

Leading to More Modern Times

In 1866, 280 acres including the present-day River Farm were sold to three men known as “The Syndicate.” A writer from The Washington Sunday Star visited the estate in 1904 and referred to it as “this broken and pathetic house.” The Wellington property was subsequently purchased in 1912 by Theresa Thompson, a member of a prominent local family that owned and operated Thompson’s Dairy, a business active in the area until the 1960s. Thompson made changes and improvements at Wellington, but it was Malcolm Matheson, who bought the property in 1919, who transformed it into the charming early 20th century country estate it is today. The evocative 18th century-style paneling in the ground floor rooms, the welcoming foyer, and the light-filled ballroom were all part of Matheson’s reconstruction of the house. Out-of-doors he cleared acres of honeysuckle, briar, and blackberry to plant boxwoods, magnolias, wisteria, and other ornamentals to create a serene park-like setting for his family.

The Russians Offer to Buy River Farm

Wellington faced one more upheaval. In 1971, Matheson decided to sell his home, and the Soviet Embassy offered to buy the property for use as a retreat or dacha for its staff. In the lingering Cold War, many people, locally and across the country, objected to the thought of George Washington’s farm becoming the possession of the Soviet Union. As a result, Congress and the Department of State asked Matheson to withdraw the property from the market.

Among those concerned by the potential sale was Enid Annenberg Haupt, a New-York based philanthropist and gardener. Through her exceeding generosity, the Society was able to purchase the 27 acres then comprising the Wellington estate. In honor of George Washington, one of our nation’s first great gardeners and horticulturists, the property was again named River Farm. In 1973, AHS moved its headquarters from the city of Alexandria to River Farm. First Lady Pat Nixon joined Haupt at the dedication of the property and together they planted a ceremonial dogwood tree in the garden.

Current Times and Looking to the Future

Since 1973, thousands of dedicated volunteers and generous benefactors continue to invest their time and resources in transforming River Farm’s grounds and buildings as “the home for American horticultural excellence.” Visitors from all over visit River Farm every year, taking in the splendor of its unique flora, manicured grounds, breathtaking Potomac River views, and reflecting on its remarkable history.

Since 1973, thousands of dedicated volunteers and generous benefactors continue to invest their time and resources in transforming River Farm’s grounds and buildings as “the home for American horticultural excellence.” Visitors from all over visit River Farm every year, taking in the splendor of its unique flora, manicured grounds, breathtaking Potomac River views, and reflecting on its remarkable history.

As the American Horticultural Society celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2022, and 50-years stewarding River Farm, AHS is affirming its commitment to the preservation of River Farm as “America’s Home for Horticultural Excellence” through numerous revitalization programs. Top priorities include re-imagining and improving the gardens and grounds with the goal of creating a landscape that is befitting the idyllic and historic property along the Potomac River. We cordially invite you to join us in celebrating AHS and River Farm while forging a vibrant future for generations to come. If you would like to help support AHS’s mission and River Farm, please click here.

For more information about River Farm we recommend the resources that can be found through the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon Estate.